For a long time, Brazil had many struggles politically which resulted in a subpar healthcare system. It was said that the only way to get the government’s attention was to die. Near the end of the military dictatorship the idea of “health for all” began to emerge. Then with the process of reintroducing democracy came a constitution in 1988, which enshrined health as a citizens’ right and which requires the state to provide universal and equal access to health services. The Brazilian health system, known as SUS (Sistema Único de Saúde) was then created. More reforms came in 1996 that established a health system based on decentralized universal access, with municipalities providing comprehensive and free health care to each individual in need financed by the states and federal government.

The SUS has three main principles. The first being the universal right to comprehensive health care at all levels of complexity (primary, secondary, and tertiary). The second is decentralization with responsibilities given to the three levels of government: federal, state, and municipal. Lastly, the social participation in formulating and monitoring the implementation of health policies through federal, state, and municipal health councils. At the national level the Ministry of Health is responsible for policy development, planning, financing, auditing, and control. At the State government level duties include regional governance, coordination of strategic programs, and delivery of specialized services that have not been decentralized to municipalities. Municipalities mostly handle the management of SUS at the local level, including cofinancing, coordination of health programs, and delivery of health services. The different health councils and health conferences are comprised of 50% community members, 25% providers and 25% health system managers. They are responsible for deliberating public health policies and monitoring them.

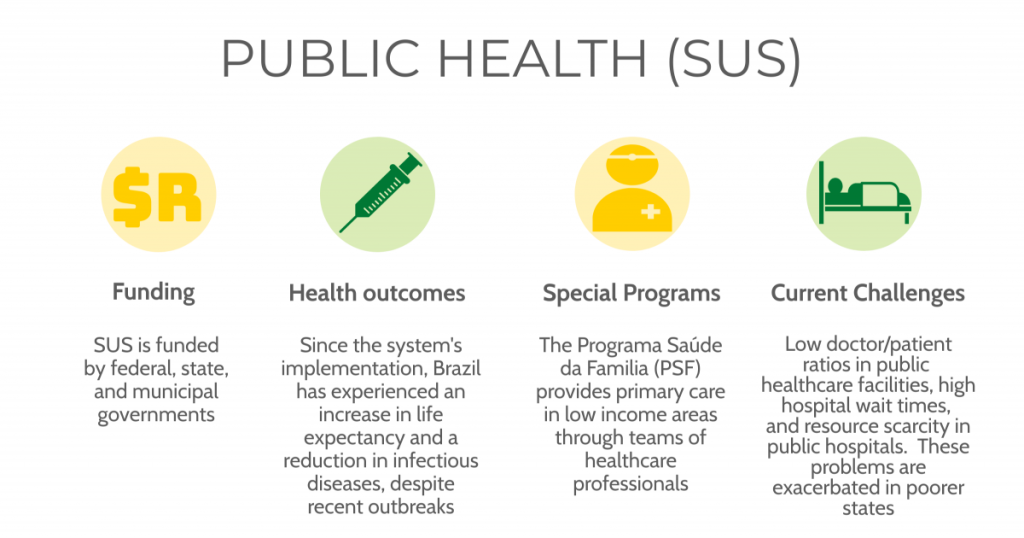

SUS covers all types of health care for all residents and visitors, even those who are undocumented. There is no application process needed to access health services. Around 75% of Brazilians get their sole healthcare through SUS. Brazil’s public healthcare system is financed by tax revenues and social contributions from all three levels of government. There is a minimum contribution defined by law: Federal 15% of net current government income, State 12% of total revenue, Municipal 15% of total revenue.

Free health services covered under SUS include: home care, organ transplant. oncology services, mental health care, maternity care, immunizations, primary care, outpatient services, hospitalizations, among many others. Despite the numerous free services out-of-pocket costs are still rather high and disproportionately affect the poor. In 2014, a little over 5% of households had such high health costs that they had to forgo paying for non-health-related items. The cost of medications was a main contributor, since only some drugs are available free of charge under SUS. There have also been steps to lower the cost of medications by increasing the amount covered to 869 in the last decade.

The main reasons that some middle- and upper-income households choose to get supplemental private insurance is due to long wait times and wanting a higher quality of care. Private health insurance is regulated by the National Agency of Supplementary Health. In 2018, 23% of Brazilians had private medical insurance. Around 70% of beneficiaries receive private health insurance as part of their employment. Typically, private health plans offer health care services through their own facilities. Copayments for private health plans have nearly doubled in the last 10 years with no limits on how much they can charge.

Over the years there has been a few different ways Brazil has tried to ensure the quality of care. One being in 2011, the Ministry of Health created a program for improving access and quality in primary care. The program included around 39,000 family health teams and was voluntary. As a financial incentive to improve quality, family health teams would receive additional payments based on evaluations, performance and interviews. Brazil has also tried to limit disparities within healthcare. Health policies have been implemented to improve equity and reduce disparities for black Brazilians, LGBTQ+ groups, the homeless and people living in rural communities. There have also been attempts to add gender reassignment coverage to SUS. The expansion of primary care has led to big improvements in access and health outcomes. Despite the huge strides Brazil has made to its healthcare, it still has a way to go with limiting costs and the occasional government caused stagnation.